IN FOCUS: Climate change isn’t a 'side of desk' activity, yet corporate efforts to bolster resilience are failing to keep pace with worsening climate impacts - BusinessGreen Intelligence's latest trend report explores how firms should respond to escalating climate risks

"The wolf is at the door," warns Greenpeace UK's head of politics, Rebecca Newsom. "Forget distant tropical islands and future generations - we have already seen what 40C summers and flash flooding look like here in the UK," she adds, in response to this month's IPCC Sixth Climate Assessment - the first comprehensive IPCC report in nine years, and the first since the Paris Agreement.

With greenhouse gas emissions still rising and the world on course to overshoot both the 1.5C warming goal and the 'well below' 2C limit set out in the Paris Agreement, there is little doubt that wolf-proofing is going to pose a defining challenge for private and public sectors alike. As the IPCC's report makes painfully clear, even if governments deliver on their promise to decarbonise the global economy by mid-century, the climate will become more hostile with droughts, heatwaves, floods, and storms all expected to become more frequent and intense in the coming decades. Fail to deliver on net zero goals and vast swathes of the global economy could soon face genuinely catastrophic climate impacts and cascading systemic risks.

And yet, while growing numbers of governments and businesses are now working to cut their emissions and deploy clean technologies, efforts to bolster climate resilience and adapt to worsening climate risks are rarely prioritised. As today's latest report from the Climate Change Committee makes clear, the UK government has wasted much of the last decade singularly failing to improve the country's climate resilience. The UK is by no means alone in this potentially disastrous oversight.

Addressing the recent UK Climate Resilience Final Conference, Sir Duncan Wingham, executive chair of the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), stated that while "all of the focus" thus far has been on mitigation, it is really important businesses and policymakers do not lose sight of the need to adapt to new climatic realities.

"We own three per cent of the mitigation problem, but we own 100 per cent of the adaption problem," he said at the event to wrap the near £19m UK Climate Resilience Programme (UKCR) - a four-year scientific research programme led jointly by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the Met Office with NERC. Spanning more than 60 projects across natural and social sciences and the engineering sector, the programme was launched to better understand how to quantify climate risks and build resilience. Speaking alongside Wingham, UKCR champion Kate Lonsdale reflected that the programme has collated a "great deal of evidence" around how climate impacts are affecting all sectors of society - and the risks will only increase.

"In even the most optimistic scenarios of reduced greenhouse gas emissions we will have to adapt our world to increased variability through improving our capacity to deal with change and make decisions, despite uncertainty as to what the future climate might be like," she said.

Political context: ‘abject failure' and a potentially ‘enormous price'

This realisation is a vital step forward, but there are widespread concerns that the message is still struggling to cut through with both policymakers and business leaders.

Swenja Surminski, a member of the UK Committee on Climate Change's (CCC) adaptation committee, points to the Joint Committee on National Security Strategy in October 2022, which described the lack of government action in response to the CCC's recommendations on climate adaptation as an "abject failure". "If we do not invest time, efforts and resources in climate adaptation - particularly to enhance the resilience of our critical national infrastructure - then there will be an enormous price to pay in future, and that price will not only be paid in money," the report stated.

The most recent report from the CCC was similarly damning, accusing the government of delivering an adaptation strategy that is "chronically underfunded and overlooked". The report argued that the UK is already experiencing severe climate impacts that are resulting in significant economic costs, highlighting the example of last summer's record-breaking heatwave which led to a spike in heat-related deaths and had a major impact on agricultural yields. It also warned that delivering a strategy that is fit for purpose will require considerable investment.

"The country's adaptation investment needs already include preparation for flooding, future proofing of infrastructure and housing, investment in public water supply and nature restoration," the report stated. "In these areas alone, it's plausible that new investment of the order of £10bn per year will be needed to prepare the UK for expected climate change. That figure could rise further with more dangerous levels of global warming."

Surminski argues that to date improvements in risk assessment have not been matched by action on adaptation, warning that despite an arsenal of tools to help keep the wolves from the door, many are currently underutilized, underfunded or inefficiently implemented. The UK needs integrated climate resilience solutions and infrastructure - such as an adaptation research centre, more funding, and robust standards - if it is to build on the UK's "world class" climate risk research, she insists.

There is a legal framework that is meant to guard against the government's worrying inaction. As Gideon Henderson, chief scientific officer at Defra, explains the 2008 Climate Change Act represented a "big step change" in the government's approach to climate change, introducing long term emissions goals, the system of five yearly Carbon Budgets that require governments to develop credible decarbonisation plans, and the CCC. Less well publicised, however, were requirements in the Act covering climate adaptation, which tasked governments with formally assessing the risks from climate change and decide how they would respond every five years.

Climate change risk assessments were subsequently published in 2012 and 2017 with the third in January 2022 setting out 61 risks to infrastructure, human health, nature, and vital systems such as food, transport system and opportunities.

The government is required to respond to the latest risk assessment with a new National Adaptation Plan in the summer - providing a crucial opportunity to update the previous plan from 2018 and turbocharge an approach to climate resilience that has been widely condemned as being badly underpowered. The big question is whether the opportunity will be seized or whether climate resilience will remain the poor relation to the government's decarbonisation efforts.

Business state of play: Perfect storms looming?

In fairness to the government, its underpowered approach to climate resilience is mirrored across much of the private sector.

Surminski explains that the private sector has a major role to play in realising the adaptation opportunities presented by the next National Adaptation Programme through green finance and investments, the development of more resilient infrastructure and buildings, insurance industry innovation, sustainable supply chain initiatives, and efforts to plug skills gaps by training the next generation of climate experts.

There is a compelling business case for such programmes. While sustainable business planning to date has largely focused on reducing carbon emissions, the inevitable impact of climate change on economies, livelihoods, and assets, mean it is paramount that businesses think about how they can adapt to climate shocks. The risk of disruption to supply chains, distribution networks, and critical infrastructure all needs managing, while the structural risks to the insurance industry requires urgent attention. Ultimately, it is much cheaper to build a climate resilient building or train track than to repair or upgrade it in a few years' time when it is hit by extreme heatwaves or floods.

And yet, there is a widespread consensus that corporate efforts to bolster climate resilience are, in the words of Margarita Skarkou, principal at urban tech sustainability fund 2150, failing to "keep pace" with the worsening reality of climate risks. And the costs are adding up. As the latest update from insurance giant Swiss Re confirmed, global insured losses topped $100bn for the second year in a row in 2022.

Sophie Stephens, head of environment and sustainability at grounds maintenance company Ground Control, warns that more regular extreme temperature events, flooding, and water scarcity will directly impact business operations. "Failure to plan how to mitigate the full impact of these events - which include facility closures, production delays, disruption to supply and distribution chains, damage to products, increase in operational and capital costs on operations - has serious consequences for the bottom line," she warns.

Skarkou adds that businesses influenced or directly dependent on the natural environment or weather patterns will, of course, be most vulnerable to climate impacts. "Those businesses that currently operate in highly carbon intensive, or natural habitat encroaching areas are the ones that face a greater need to adapt," she says. "Adaptation is fundamentally about making businesses more resilient but also society and our communities more resilient over the medium to long term - and, in some cases, near term."

To this point, Dr David Pugh, head of sustainability at the Digital Catapult, the UK hub for innovation in advanced digital technology, adds that that the climate crisis continues to demonstrate the fragility of UK supply chains. "Businesses will need to secure their supply chains while meeting growing expectations from both government and customers on sustainability and mitigating the effects of climate-related shocks," he explains.

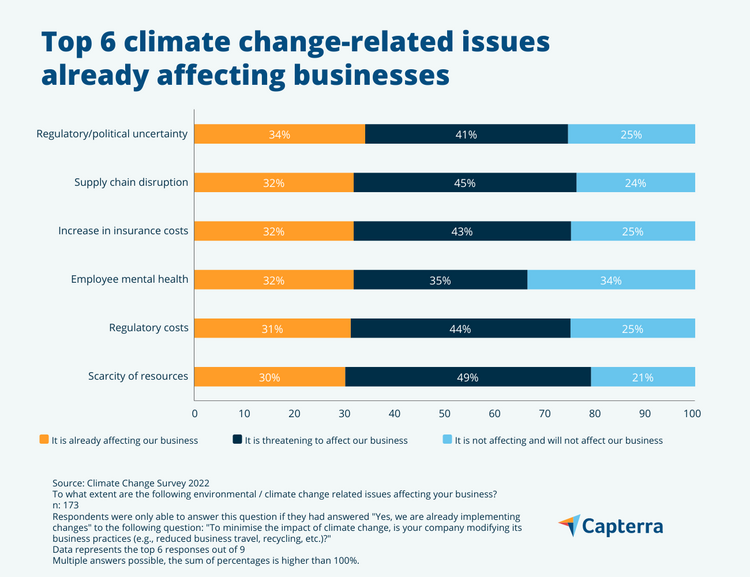

And the risks are not limited to the obvious physical impacts associated with a washed away train track or parched crops. Eduardo Garcia Rodriguez from climate software directory Capterra UK flags how regulatory, reputational, and financial risks are also likely to increase alongside physical risks. "UK businesses need to comply with government regulations, including emissions limits and waste reduction targets," he says. "In our recent climate change survey for UK SMEs, we saw that 36 per cent of businesses deploying climate change mitigation strategies were doing so to comply with government regulations. As consumers become more environmentally conscious, SMEs can also risk losing customers and receiving bad publicity if they do not address climate issues. Thirty-eight per cent of surveyed SMEs carrying out climate change strategies did so to meet external expectations, and 35 per cent did so to enhance their brand reputation."

Even businesses that invest in more climate resilient infrastructure could still be hit by the economy-wide fall out from more intense climate impacts. "Climate change can impact corporate finances and bottom lines through higher insurance premiums and increased costs associated with transitioning to a low-carbon strategy," Rodriguez warns.

Faced with all of the above, Bob Gordon, forum director at the Zero Carbon Forum - a membership-based, non-profit organisation working with the UK hospitality sector - believes food production is just one of many sectors on the cusp of a "perfect storm".

"The world population has just passed eight billion people, coupled with an increase in demand for more meat and protein worldwide, and the sector needs to produce significantly more food," he says. "At the same time, conditions are changing rapidly, with an increase in extreme weather events, including drought and flooding, which is impacting growers abilities to produce food. On top of that, the food sector is going to have to radically reduce production emissions in order to meet emissions reductions targets set by governments and the private sector."

What innovation is already happening?

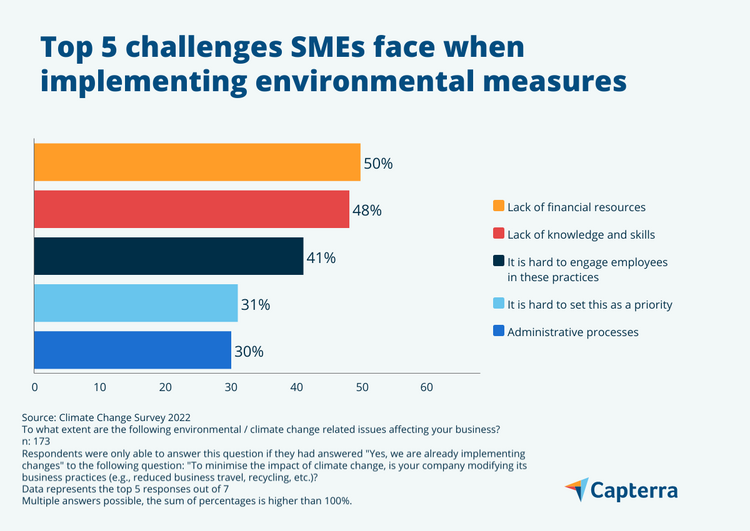

How then can businesses respond to these complex and interrelated risks? How can they accelerate their still underpowered decarbonisation efforts at the same time as bolstering climate resilience, especially when governments are routinely failing to provide the necessary policy frameworks and underlying infrastructure investment?

The good news is pockets of climate resilience and adaptation innovation do exist even if they are far from endemic. Gordon - who led Nando's sustainability and social responsibility agenda in the UK and Australia for eight years and is a non-executive director of environmental communications charity Hubbub UK - has witnessed significant activity to boost climate resilience within his own sector, for instance.

"Companies are reducing their scope one and two emissions through energy efficient equipment, behaviour change and purchasing of renewable energy," he says. "Not only does this reduce emissions, it also reduces costs - making businesses more resilient to the current high energy prices. And when it comes to sourcing food, there is a lot of cross over between reducing emissions and building resilience. For example, regenerative agricultural practices typically reduce carbon emissions, as well as improving soil health, biodiversity, and water management. Honest Burgers, Gaucho Restaurants, and McDonalds are all sourcing beef from regenerative sources and/or running trials on the impact of doing so, WSH and Pizza Pilgrims are both sourcing regenerative wheat from Wildfarmed, and the majority of operators are introducing more plant-based options on their menus."

The shift towards more plant-based diets is a particularly pertinent example of how interconnected climate mitigation and adaptation policies should be. Not only does it help reduce emissions, it can free up land that can be returned to nature which can in turn help reduce flood and drought risks. Similarly, plant-based diets and regenerative agricultural practices tend to require shorter supply chains, which should serve to further reduce exposure to climate impacts.

Andrew Coburn, co-founder and CEO of climate analytics firm Risilience - a Cambridge-based tech firm that was spun out of the university's Centre for Risk Studies - has similarly witnessed a burst of innovation, ranging from replacing liquid products with concentrates and powdered versions to reduce both carbon footprint and water use to the adoption of regenerative agricultural practices.

"A notable example of this is businesses partnering with farmers to plant protective trees to provide shelter and shade for sensitive crops that would otherwise reduce their yield as a result of increased temperature and transpiration from climate change," he says. "Instead of buying crops as commodities on the open market, the large corporate customer is partnering with farming suppliers to protect their livelihoods and sustain future supplies of key agricultural raw materials."

Another common tactic that can both reduce emissions and bolster climate resilience is to be found in the shortening of supply chains. "We are seeing businesses taking the decision to nearshore or onshore their supply chains and restructuring to place production or processing closer to the customer," Coburn says. "This ultimately reduces the distance needed to transport finished goods, reducing transportation fuel and overall carbon footprint."

Emerging factors: extreme weather, litigation, migration

However, such innovations remain the exception rather than the rule, with the vast majority of businesses remaining blind to the escalating climate risks they face. Meanwhile, many investment decisions and infrastructure projects are failing to properly account for changes to the climate that are now inevitable.

According to Wingham, even if the world does manage to stabilise the climate by 2050, it will be far removed from the conditions we see today. "If we're thinking about how to do mitigation, we've got to be thinking about solutions which are appropriate for the climate of 2050 and not the climate in 2020," he advises.

Maria Sunyer, climate risk expert at climate consultancy EcoAct, concurs, warning that while some physical climate-related risks like flooding are well known to the UK - an estimated total of 1.3 million people in England alone already live in areas of high risk of flooding with associated damage costing approximately £700m a year - others could be considered new or emerging threats. She cites the increased risk of overheating or wildfires during last year's record summer temperatures of over 40C as evidence of an entirely new climate threat for the UK, for example.

There is a compelling case for infrastructure, including enhanced coastal flood defences, to be developed in line with projected impacts. But while such thinking is increasingly embedded in major infrastructure projects, planning rules continue to allow for the development of homes that are located in flood risk zones and are prone to overheating during summer heatwaves.

Extreme weather also triggers second order impacts that can pose just as big a threat to businesses and investors.

For example, Sunyer flags a relatively new challenge posed by the rise of climate litigation. "Since 2015, climate change-related cases have more than doubled - a quarter of the nearly 2,000 cases filed so far globally occurred between 2020 and 2022," she says. "Climate litigation has so far mainly focused on holding both public and private organisations accountable for their climate mitigation efforts - or lack thereof. But as businesses continue to contribute to the rising costs of climate adaptation, we can expect to see an increase in lawsuits looking at holding them accountable if their adaptation efforts fail to contribute to global needs, protection of biodiversity or delivery of co-benefits such as green job creation and positive impacts on public health." It is very easy to envisage future legal action against companies that sold buildings or products that failed to account for climate impacts that were entirely foreseeable.

And then there are the big picture geopolitical and macroeconomic risks. Looking further ahead, Ground Control's Stephens forecasts that climate migration will drive people towards cities, forcing businesses to consider how more urban-centred societies will impact supply chains and business models. "In August last year, one third of Pakistan was underwater, with the World Bank estimating that 216 million people could be displaced by 2050," she explains. "The war in Ukraine has shown how reliant businesses are on global economies - the impact of large-scale migration is likely to be far greater."

‘Place matters'

The challenge for businesses and governments is that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to the climate adaptation challenge.

Wingham stresses that different regions all carry bespoke "special needs", thereby creating an intricate patchwork of physical and socio-economic challenges. "Adaption like mitigation is a problem for everyone, and as soon as you say that you immediately open the door to all the complexities that the word ‘everyone' implies," he says. "Place matters. Place is not a theoretical thing, it's a literal thing, and there are literal places with literal needs and they're all different."

2150's Skarkou warns that local context plays a "key" role in adaptation in a way that it is not always the case for climate mitigation projects. "Coastal communities are likely to be far more impacted by climate change than landlocked regions," she predicts. "Similarly type of business matters as those relying on or working with natural assets are likely to be more affected."

As an example of these localised complexities, a recent report from consultancy giant McKinsey & Company found that four-in-five of the world's 510 million smallholder farmers are disproportionately exposed to worsening climate hazards. The report set out a detailed menu of more than 30 potential adaptation measures that such farmers could take, with precise recommendations likely to vary massively based on the specific risks and opportunities an individual farm faces.

However, there are some universal best practices to draw on. The report - titled What climate-smart agriculture means for smallholder farmers - urges policymakers to develop land management plans geared towards addressing climate hazards, increase access to crop insurance and food security planning, and use taxes, subsidies, and other incentives to encourage more sustainable farming practices and steer smallholders towards adapting to the risks most prevalent in their region.

The report explains that its top 10 mitigation measures highlight said regional differences. It flags, for example, that while roughly half of smallholder farmer-driven agriculture emissions in India could be mitigated by scaling agroforestry practices and transitioning to more sustainable rice production techniques, in Ethiopia and Mexico, where cattle production systems are more common, livestock-related measures dominate and could collectively mitigate up to 25 per cent and 35 per cent of emissions, respectively.

"Priorities for adaptation differ by country," McKinsey states. "These differences are mainly driven by varied exposure to climate change hazards and by the farming systems used in the exposed areas. For example, using drought-tolerant seed varieties is much more applicable in drought-prone India or Mexico than in Ethiopia. This is because pastoral livestock systems dominate the drought-prone regions of Ethiopia rather than crop production.

"Moreover, more farmers in India - 95 per cent of the total - are exposed to at least one risk, and most are exposed to multiple risks, which requires the adoption of multiple adaptation measures. In Ethiopia, on the other hand, 37 percent of farmers are exposed to at least one risk, and few face multiple risks."

Closer to home, Christopher Walsh of the University of Manchester, who contributed to the UKCR Programme, highlights how the UK's historic building stock presents a particular climate resilience challenge. He highlights the experience of the Church of England, which is looking to enhance its climate resilience as part of an ambitious plan to hit net zero emissions by 2030, but is faced by the "inherent complexity" presented by an estate of 16,000 religious buildings, some 78 per cent of which are listed and span centuries of construction practices all informed by different regional or denominational blueprints.

While churches are often placed at the highest point of villages and are therefore protected from flooding, many are susceptible to overheating and storm damage. Cultural and religious sensitivities also contribute to an already complex puzzle, according to Walsh. A church in Wennington, Kent, for example narrowly escaped climate disaster amid wildfires triggered by record summer temperatures in 2022. While Walsh explains that there are often sensitivities around mowing the grass in graveyards and cutting back meadows in church grounds, he says that had authorities not mowed the graveyard a week before the wider community was hit by a blaze, the church would have burned to the ground.

However, while local communities often struggle to raise funds for building upgrades, Walsh cites one estimate from the UKCR programme that revealed how it can cost approximately 8.7 times more to make climate-related adaptations if authorities wait for buildings to fail, rather than literally fixing the roof while the sun is shining.

Where to start?

Businesses should use as many resources as possible to boost their adaptation efforts, according to 2150 principal Margarita Skarkou, taking advantage of "all that is available to them".

"A good place to start for any business wanting to learn more about adaptation and what it means for the UK, is the CCC's Adaptation Committee Independent Assessment of Climate Risk," she says. "Businesses should be able to use and interpret this report to start deciding what the key risks for their own operations are. Another useful resource for businesses includes the UK government's 'Build Back Better' plan, which offers a lot of general support for SMEs on ESG output currently. Increasingly, we'd expect adaptation to form part of this plan."

There are also avenues for securing more locally tailored support. "Local authorities should have resources and can be well placed to provide support," says Skarkou. "Most Land Associations should be starting to think about what adaptation means for their locality, if they don't already have a plan. Banks should also be able to support with some of those discussions. Funding to make a business more resilient for the long run is a worthwhile investment, particularly if a pivot can enable business to benefit from the changing climate economically whilst becoming more resilient to shocks."

Capterra's Rodriguez also highlights that almost £5bn of funding is available to help UK businesses become greener as part of the government's commitment to reach net zero emissions by 2050, while organisations such as The Catapult Network - backed by the UK's national innovation agency, Innovate UK - run regular accelerators to foster sustainable innovation alongside larger projects to help businesses to embrace sustainable innovation, covering climate resilience as well as decarbonisation.

EcoAct's Maria Sunyer adds that invaluable adaptation advice and support is contained in the growing body of evidence on how climate change will affect the UK and its business sector. For example, she claims large scientific research programmes such as UKCR, the EU Taxonomy - which will inform the UK Green Taxonomy - and ISO standards 14090 and 14091 offer guidance on how to conduct climate risk assessments and develop adaptation measures.

"In addition, resources and publications from the CCC provide insights on how the UK is preparing for climate change, which can help inform decisions on adaptation strategies at the corporate level," she continues. "If we look further afield, there are also international platforms such as Climate-Adapt, which aim to support Europe in adapting to climate change by providing useful resources to help organisations understand climate risks and identify solutions."

Moreover, many large organisations are now mandated to report on climate-related risks and undertake scenario planning in line with the recommendations from the Task-Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). Simon Weaver, partner and co-head of climate risk and strategy at KPMG in the UK, urges businesses to familiarise themselves with disclosure frameworks to understand climate-related risks and how to respond.

"There are now over 4,000 companies globally that have adopted TCFD, representing a market cap of $28tr, but more still needs to be done," he says. "Understanding the purpose and drive of these disclosures is a crucial step for considering what actions a business needs to take. But there's a lot out there, and we recognise it can be a complex landscape to untangle."

And then there's the insurance industry, which has an obvious financial incentive to work with its corporate clients to encourage them to build more climate resilience infrastructure and embrace adaptation measures.

Changing adaptation data, modelling and tech

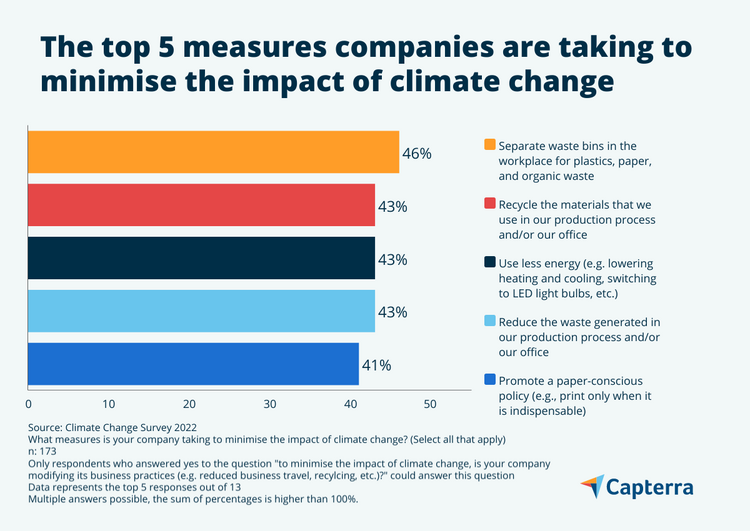

Climate adaptation strategies will inevitably vary massively by geography and industry, but for Capterra UK's Rodriguez, a solid climate resilience strategy should feature regular risk assessments, investment in more resilient solutions such as renewable energy and greener buildings, engagement with suppliers, and regular progress reports to stakeholders. "Different software can help them to achieve this," he says. "For example, risk management software can be used to identify and mitigate climate risks, while compliance software can help meet regulatory targets."

The Digital Catapult's head of sustainability, Dr David Pugh, similarly highlights the role of emerging digital technologies in helping firms get a grip in a fast-changing risk landscape. "Technologies, particularly data analytics, can enable businesses to become more climate resilient by providing predictive insights that allow for informed decision-making," he says. "For example, ClimateX, which Digital Catapult supported on its Machine Intelligence Garage programme, is leading the way by delivering climate risk analytics through a combination of science and econometrics."

Met Office service director Simon Brown adds that efforts to improve climate hazard information and thereby provide more useful risk analytics have revolved around using greater data capabilities to enhance the representation, characterisation, and ultimately the understanding of climate hazards For example, he explains that scientists have recently been able to get a much more granular understanding of climate risks and impacts. Adding "covariates" such as latitude, longitude, and distance to coastline, and tracking their interaction with climate impacts has allowed the UKCR project to model different types of data simultaneously and paint a more vivid and accurate picture of extreme events.

Granular data can also be applied to corporate supply chains to better understand where climate risks may pose a threat. "We partnered with Circulor to trace risk materials throughout our complex supply chain," explains Fredrika Klarén, head of sustainability at electric vehicle manufacturer, Polestar. "The blockchain-powered traceability solution means we can identify areas of our supply chain that could be causing environmental and social harm and take immediate action to resolve this. We include this data in a customer facing product sustainability declaration, easily allowing to compare sustainability credentials along with other factors such as price and range in the buying process."

Klarén also claims that Polestar was the first automaker to release a life cycle assessment along with full methodology for a vehicle. "The life cycle assessment includes the extraction and refining of raw materials, manufacturing of parts, manufacturing of the car, inbound and outbound logistics, use phase, end-of-life and provides methodology for how we calculated," she says. "This radically transparent approach holds us to account and ensures sustainable methods are prioritised from the very beginning of the car making process."

Embracing best practices

According to the Digital Catapult's Dr David Pugh, there is ultimately "no right way" to establish climate resilience. "How an individual business deals with climate change depends on several factors such as its location, size, supply chain, and energy sources," he says. "To ensure comprehensive preparedness, a roadmap should consider potential climate risks, backup options, and worst-case scenarios, while also prioritising solutions that leverage emerging technologies to address these challenges."

Though climate risk assessments have been improving in recent years and businesses are gradually gaining a better understanding of physical and transition climate risks, there is still work to be done to better understand risks and related uncertainties while compiling a plan of action.

"First, we need to take a holistic approach to assessing risk," says EcoAct's Maria Sunyer. "Look at physical and transition risks but considering both direct and indirect risks to operations and value chains as well as interdependencies. It is important to assess risk within the current context of the business, but also with a view to the future."

Once businesses have identified physical risks, such as operational disruption, supply chain complications, labour concerns, insurance costs, they then need to establish potential impacts and how they intend to manage the sharpest of these.

In an ideal world, businesses should identify "no-regret" actions that are cost-effective now and under a range of future climate scenarios, while contributing other social, economic and environmental benefits, Sunyer advises.

"Consider a wide range of measures - strategic, operational, and physical - and most important, consider also uncertainty," she says. "Uncertainty is inherent in climate change, making it harder to understand what the impacts will be or when they will happen. But here is where climate modelling tools play a crucial role. They can help us make projections of future climate change and thereby inform adaptation and mitigation decisions."

However, understanding such risks is of little value if businesses fail to then act on them. "This process of assessment and identification of risks and measures needs to materialise in an implementation plan, where businesses' main mission is to build adaptation into existing processes, engaging the board and different departments as well as relevant stakeholders," Sunyer continues.

There is also a need to repeatedly iterate the strategy. "Climate adaptation is not an objective or end point," Sunyer warns. "It should not be seen as a linear process. It requires regular monitoring to ensure measures in place are effective and provides also the opportunity to assess if adjustments or additional measures are needed."

As such, Capterra UK's Eduardo Garcia Rodriguez, says that it's crucial that companies set objectives and monitor their progress in implementing climate risk management measures. "There should be transparent reporting on actions to stakeholders, investors and employees," he says, "This can help build trust and demonstrate a commitment to sustainability."

For KPMG's Simon Weaver, when it comes to managing risk and implementing adaptation plans, it is important to consider reforms that are "both top-down and bottom-up".

"From the top, climate change has the potential to exacerbate and affect principal risks, and an in-depth view of how this could manifest can support businesses to understand the full sweep of its impacts," he says, "From the bottom, businesses should be integrating climate into operational response planning, readying sites and employees for potential impacts.

"The crux of it is that climate change isn't a ‘side of desk' activity - it's imperative for successful future business strategy."

Lower cost adaptation

With businesses squeezed by high interest rates and energy costs, adapting to climate change is regularly seen as an inconvenient expense, according to Sunyer. However, she explains there are a number of important and cost-effective steps that businesses can take towards greater resilience, as well as a compelling long term business case for undertaking more capital-intensive investments.

"While adaptation actions help us build future resilience across business' operations, they can also bring multiple benefits, such as increased productivity and innovation, regardless of whether or not climate change-related risks and extreme events occur," she says.

Ground Control's Sophie Stephens adds that businesses need to look at three key areas to improve their climate resilience: assets, operations, and value chains.

"Consider the potential risk of extreme weather like flooding, freezing or fire to your assets and build in the additional cost involved in keeping them warm or cool," she says. "High temperatures may require more night working or longer days with businesses closing during the hottest hours in the middle of the day - this will have implications for a business' operations. And in the value chain, it is essential to have a detailed understanding of where materials are sourced from and how sensitive producing and transporting them are to the impacts of climate change."

Pugh adds that while bolstering the resilience of assets is crucial, diversifying revenue streams can also act as a potential climate risk safeguard. "This includes considering ‘servitisation' as a business model," he explains. "Embracing this can yield great success, being both a cost-effective and commercially viable solution for businesses looking to mitigate climate-related risk… A servitisation business model can improve climate resilience by reducing overall resource consumption and environmental impact, extending the lifespan of products, and building sustainable business practices," he adds.

However, KPMG' Simon Weaver adds that ultimately adaptation challenges may necessitate "organisational transformation", aligning people under a common ambition and ensuring robust internal processes to measure, manage and respond. "In some ways, it can cost almost nothing to reorganise your business to meet the challenges head-on," he says. "And it can be an extremely effective way of improving business resilience to climate risks, whilst also engaging talent across your organisation and beyond."

Climate risks are ‘core business risks'

Ultimately, Swenja Surminski of the CCC's adaptation committee suggests three key principles to guide businesses as they guard against the climate "wolf" at the door.

Firstly, she urges climate leaders to engage with forward-looking trends. "Strategies need to incorporate information on climate change projections and evolving risk drivers to minimize the risk of maladaptation, blind spots, and lock-ins," she told the recent UK Climate Resilience Final Conference. Infrastructure that is suitable for the 2020s will not be suitable for the 2040s.

She also advised that there is an urgent need to collaborate both within and between industries. "New models of participation can coordinate action and align incentives among a wide range of stakeholders, such as corporates, households, communities and governments," she added.

Finally, Surminski states that climate leaders should aim for adaptation measures that have knock-on effects across their business by taking a "systems-level" approach to resilience in their climate strategies. "Leveraging a broad range of social, economic and environmental co-benefits can strengthen the business case for resilience and unlock investments," she said.

EcoAct's Sunyer concludes that while climate change may sometimes feel like a far-off threat - whether confined to distant tropical islands or future generations - it is crucial to recognise that it is already affecting every region on Earth and impacting all industries either directly or indirectly and that action is urgently needed.

"Climate adaptation is crucial and acting on it now will reduce costs and negative impacts in the long term," she says. "Climate risks should be considered core business risks. "Business leaders must act now, not only to mitigate the risks that come from climate change but also to take advantage of the new opportunities opening up in our transition to a low-carbon economy."

A failure to respond to this daunting reality is arguably an act of negligence and a failure of fiduciary duty. Businesses, governments, and investors cannot say they were not warned.