Schroders: We attach financial values to many assets - so why don’t we do the same with finite natural resources which our economic activity and wellbeing depend on?

The last few hundred years of human activity have stored up changes in climate that threaten human existence. But climate change is not the only ecological threat - it is widely agreed that damage to the natural environment and loss of biodiversity pose a comparable risk.

Natural resources are the single most important input to the global economy. Whether it is raw materials, water, flood protection, biodiversity or pollination, nature provides most of the capital businesses need for the production of goods and services.

Yet over the past 150-200 years, approximately 60 per cent of the Earth's land surface has been altered, primarily by agriculture.

We all have a role to play in protecting these resources so that humans can continue to benefit from it for generations to come. There is also an increasing awareness that biodiversity loss contributes to climate change and is an investment risk.

What is natural capital?

The term is used to describe elements of nature that provide important benefits called 'ecosystem services'. These include CO2 sequestration or removal, protection from soil erosion and flood risk, habitats for wildlife, pollination and spaces for recreation and wellbeing.

Nature provides critical societal benefits to individuals and communities around the world. The combination of soils, species, communities, habitats and landscapes which provide these ecosystems services are often called 'assets'.

The idea of viewing nature as natural capital, recognising the true value of nature's assets, is rapidly increasing in popularity. While the term first came into use in the 1970s, there are now growing calls for natural capital to be viewed as an economic asset, with the UN urging governments to look beyond GDP.

"Natural capital is different from other sources of capital because it's not produced," Dieter Helm, professor of economic policy and Fellow in Economics at New College, Oxford, has said. He has pointed out that oil and gas are natural resources that are derived from nature itself and are free for us to use at their starting point.

How does natural capital differ from other sorts of capital?

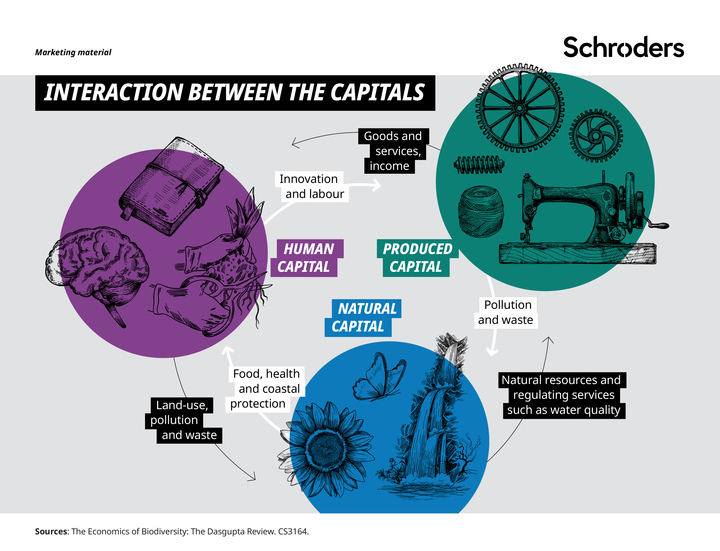

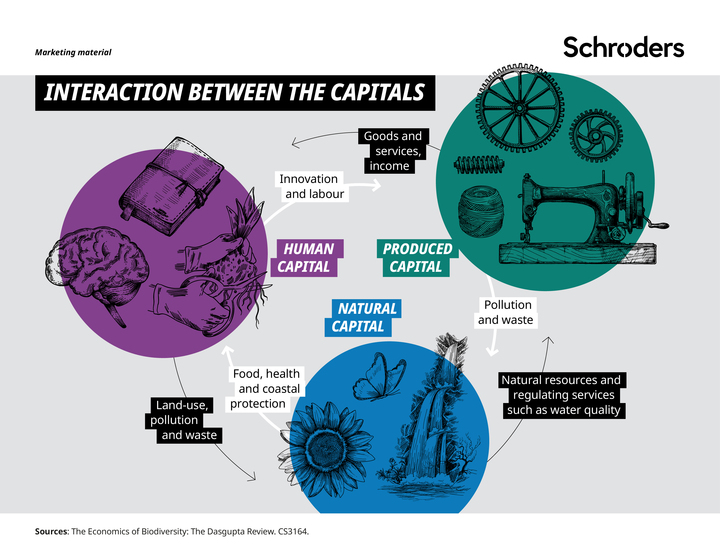

Machinery, vehicles, buildings and other manufactured items are termed "produced capital". This is "the stuff that we humans have made," Helm explains in his podcast. "We've converted the things around us into physical capital that is used in production."

So while oil and gas exist in nature, we use man-made machinery to access it and turn it into everyday products like petrol and plastics.

Human capital, meanwhile, refers to the knowledge, judgement and experience that we as humans contribute.

All three sources of capital work together and form the basis of economic activity.

How is natural capital categorised?

Natural capital can be split into renewable and non-renewable categories. Oil, gas and minerals, for instance, can only be used once.

"The issue isn't necessarily that these assets are being used," says Professor Helm. "It's that if one generation uses it up, how do we compensate future generations - because it won't be available to them anymore?"

Renewable natural capital is more forgiving. "Renewable capital, unlike other forms of capital, is capital that keeps on giving its benefits forever," Helm says.

He explains that there's a critical threshold with these assets: if you deplete its stocks past this tipping point, the capital is no longer renewable. It's crucial to maintain, enhance and protect these resources so that they are available to future generations.

What's an example of renewable natural capital?

Professor Helm, who is also a director at Natural Capital Research, points to the North Sea's fishing stocks.

"If you eat kippers or herring, you're enjoying the benefits of a renewable bit of natural capital. Provided we don't overexploit this renewable natural capital, people in 100 years' time will also be able to have kippers," he says.

As long as natural stock is not driven below critical thresholds, the assets can regenerate.

Humans and the livestock they're rearing for food make up 96 per cent of the mass of all mammals on earth."

Is natural capital the same as biodiversity?

Sometimes the terms are used in ways that suggest they are interchangeable. But 'biodiversity' applies to living organisms. Natural capital includes living organisms but also includes the flow of ecosystem services from this biodiversity.

More than 32,000 species are threatened with extinction including 26 per cent of mammals, 41 per cent of amphibians, 33 per cent of corals and 14 per cent of birds."

Is natural capital valuable in financial terms?

Natural capital is central to life as we know it - we are wholly dependent on it for our survival and development. But society doesn't officially recognise it as an economic asset. This means nature's pivotal role is not being accounted for in measurements of economic growth and wellbeing.

There are now growing calls for it to be viewed as such. The UN's landmark economic framework, the System of Environmental-Economic Accounting, will help people and businesses more accurately value natural resources.

The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity is another pioneering initiative that aims to mainstream natural capital accounting by following a structured approach to the valuation of natural resources.

Meanwhile the Capitals Coalition, which is made up of 380 global initiatives and businesses, is also trying to get most of the world's businesses, financial institutions and governments to account for natural capital in their decision-making by 2030.

Kathy Willis, a professor of biodiversity at Oxford University and another director at Natural Capital Research, said that viewing nature as an asset and putting it on the same balance sheet as a company's other resources is no longer seen as an oddity.

"Governments, corporations, and individuals across the world are starting to understand the critical importance and value of the ecosystem services provided by their natural capital assets, not least in carbon storage and sequestration," said Professor Willis. "There is huge potential of investing in natural capital assets; potential not only for offsetting of carbon and ESG but also for halting global biodiversity loss and restoring some of the most important ecosystems in the world."

Although less than two per cent of the earth's surface area, tropical rainforests are the habitat for more than half the world's plants and animals."

Should natural capital really be the concern of investors?

More than half of the world's total gross domestic product, or $44tr, involves activities that are moderately or highly dependent on nature, according to the World Economic Forum.

Andy Howard, Schroders' head of sustainable investment, says: "The degradation of natural capital, including the loss of biodiversity and depletion of renewable stocks, poses a real risk for businesses, their earnings and investors."

In practical terms this could mean business, banks and investors facing increased insurance risks, higher costs of capital and a loss of investment opportunities.

"Sectors which are overly-reliant on ecosystem services that are currently not valued, or undervalued, may see company valuations affected when these are eventually accurately valued," Howard explains. Such sectors include agriculture, food and marine.

"Furthermore, regulatory and policy pressures are already beginning to build and crystalise. For example, the EU Green Deal contains a significant element on biodiversity. These could have direct revenue impacts," he adds.

As with climate change, if nothing is done the costs could be high. The World Wildlife Fund estimates a direct cost of $10tr globally between 2011 and 2050.

How does natural capital fit with the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

In the long term the rate at which natural capital is depleted needs to match the rate at which it can regenerate, otherwise the life support systems that we need from nature will run out. The SDGs were developed on the basis that we can achieve a sustainable rate of natural capital usage.

What have investors done so far?

Biodiversity-related financial risks are not yet fully appreciated by most investors. Investors have 'limited awareness' of the issue, according to the Principles for Responsible Investment. And there are very few commitments or policies in place to address it. But momentum is gathering.

Hannah Simons, Schroders' head of sustainability strategy says: "There are efforts underway by the World Bank and global investors to establish collaborative engagement along similar lines to the Climate Action 100+. The so-called Nature Action 100+ would seek to drive change at the top 100 companies having the biggest negative impact on nature."

She points out that work has begun on a Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures with a plan to create a framework, similar to the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures, for firms to disclose their exposure to nature-related financial risks by the end of 2023.

"Science-based targets for nature are in the early stages of development by the Science-Based Targets Network," she says. "These targets are a way in which businesses can align their individual sustainability action with globally agreed environmental goals."

What more needs to be done by investors regarding natural capital?

Investors can play their part by allocating capital towards investments that preserve our natural environment and understanding how companies in their portfolios use and rely on natural capital.

Kate Rogers, co-head of charities at Cazenove Capital, which oversees portfolios belonging to foundations and charities, highlights the importance of investors working together. "We look forward to working alongside other purpose-led investors on a new collaborative engagement programme asking companies to value, protect and restore nature," she says. "We see active ownership as a key part of our action to halt biodiversity loss."

Andy Howard adds: "We can act as active owners of our investments, using available data to determine leaders from laggards and drive change, especially among laggards, to help them improve business practices".

Hannah Simons explains: "It is also our responsibility as investors to encourage third parties to collect and disseminate consistent and comparable nature-related data, and urge companies to get involved in the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures pilots".

This article is sponsored by Schroders.